Simultaneously, the annual Monsoon inundations are delayed more and more often, while still retreating early, and leaving local fields parched.

But why? Let’s unravel a complex tangle of reasons, with climate change at its core.

Deltas have always been hubs of human development. Ancient civilizations flourished in the Nile and the Ganges deltas. Today, half a billion people call deltas home—even though they cover only 1% of the earth’s land surface. With rich crops and abundant fish, deltas are crucial to food security and economic development.

However, deltas are also extremely vulnerable.

Located at the intersection of terrestrial and aquatic ecosystems, a delta’s entire existence depends on a delicate balance of factors: Temperature. Freshwater and saltwater. Precipitation and river flow.

In the Mekong delta, this balance has been disturbed. As a consequence, the delta of Southeast Asia’s largest river is both sinking and drying out at the same time. While ever-rising waves lap away at the coastline, and higher sea levels push salty water into the delta, severe droughts are leaving the landscape parched.

But what exactly causes this double threat? And what can be done about it?

The answers to these questions are as complex as the environmental and political problems casting their shadows over the region.

At the heart of the issue: Climate change.

Living with the River

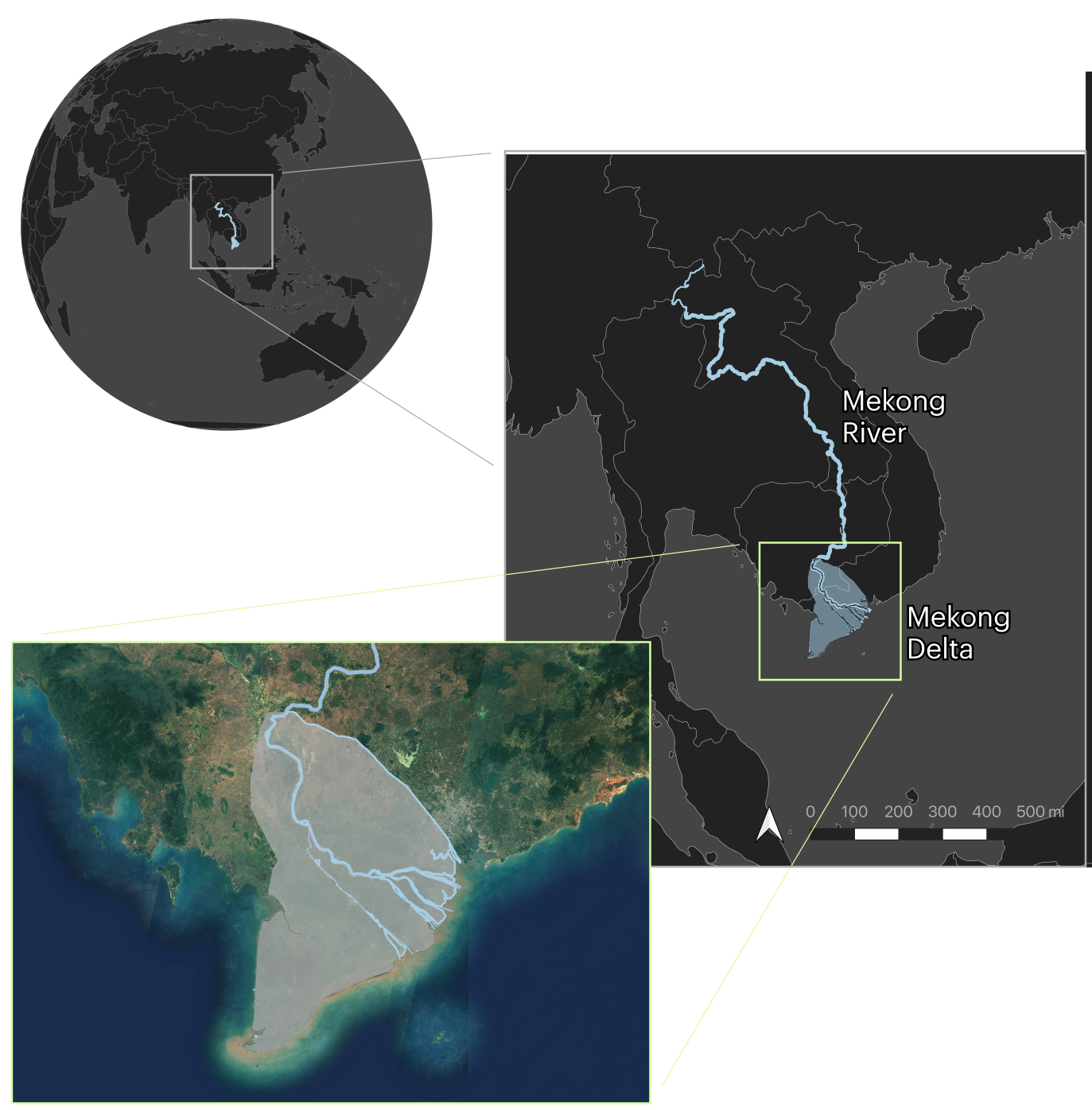

Springing from the vast Tibetan plateau at the foot of the Himalayas, the Mekong river winds its way over 2,700 miles through China, Myanmar, Laos, Thailand, Cambodia and Vietnam.

At Cambodia’s capital Phnom Penh, the river splits into branches that fan out over the fertile delta plains, defining the landscapes of southern Cambodia and Vietnam.

On these floodplains, both biodiversity and agriculture flourish. Over eighteen million people live in the delta, and it supplies over 200 million with rice, fruit, vegetables and fish. Agricultural products from the area also bolster the international exports of the countries in the region.

The abundant fertility of the Mekong delta is based on the annual Monsoon cycle.

Fed by torrential rains, the Mekong begins to swell in June, overbrimming its banks and inundating the surrounding floodplains. The land remains underwater for several months, until the flood begins to recede in October or November.

Far from being a disaster, these inundations are welcomed by the local inhabitants.

During the wet season, the delta is replenished. Fish populations explode. Water infiltrates the soil, dusty from months of little to no precipitation, and is stored in canals and lowland areas.

The sediments left behind at the end of the wet season are full of nutrients. In the rich, muddy earth that emerges from the receding floods, farmers plant rice and vegetables, marking the beginning of the new agricultural year.

This cycle is so deeply ingrained in the consciousness and identity of the people that it forms the basis of some of the region’s most important cultural traditions. In Cambodia, the Water Festival (Bon Om Touk) is celebrated in November. It marks the beginning of the flood recession with fireworks, boat races and nautical parades.

These traditions reach back to the Khmer empire of the 9th–15th century. They illustrate the central importance of the yearly flood pulse for the delta, and how it has been rooted in local consciousness for hundreds of years.

Today, the hydrological balance in the delta is shifting.

Droughts, Dams, and the Distribution of Rain

Officially, the arrival of the 2019 flood was two weeks late. During this time, the Mekong water levels dropped to their lowest in 100 years.

At the beginning of August 2019, the delta was still dry.

Endless water surfaces should have been stretching into the horizon. Instead, the bare earth of the floodplains was cracked with heat.

The flood delay in itself was already a major problem for the many farmers of wet season rice, a crop which depends on the inundations starting at the right time.

What’s worse, after the flood finally did arrive, it did not stay for long. The flood began to drain away at the usual time, spelling disaster on a larger scale. As the flood curves of the Mekong water levels show, the 2019 flood pulse was only about half as long as in past years.

The combined effects of the late arrival and short duration of last year’s flood reverberated through the landscape in a cascade of negative impacts.

While farmers did mostly succeed in growing crops directly after the flood, many of them faced worries for the rest of the agricultural year.

The flood was too short to infiltrate deeply into the soil, leaving it thirsty for irrigation. Many irrigation channels, however, were dry.

In addition to the drought, pests usually decimated by the flood now threatened crops. Rats in particular survived in far higher numbers than usual, and subsequently attacked vegetable and rice crops.

How could this all happen?

The list of causes is a long one, ranging from a dam cascade being built upstream to land use changes in the entire Mekong basin.

Climate change, too, is a critical factor.

To begin with, average temperatures in Southeast Asia have risen continuously over the last few decades, in line with global warming. In Vietnam, the annual average temperature rise has been 0.1 °C per decade since 1900, ramping up to 0.14 °C per decade towards the end of the century. Summer temperature increases are even higher, with average monthly temperatures climbing by 0.1–0.3 °C per decade.

But higher temperatures are not the only contributor to the droughts that have struck the region in recent years.

Satellite rain measurements over the Mekong basin show that macro-scale precipitation distribution in 2019 differed significantly from previous years.

The torrential Monsoon rains in the catchment area of the Mekong, which generally set in towards the end of May, were sparse in the spring and early summer of 2019.

Meteorological experts trace the immediate cause for this back to the El Niño Southern Oscillation (ENSO). Approximately occurring every four years, El Niño is a global weather event with impacts on local weather. It is caused by a change in temperature distributions in the Pacific Ocean. Oceanic and atmospheric conditions interact to invert the usual east-west direction of ocean surface winds. Now blowing from west to east, they drive warm equatorial waters towards the eastern Pacific. This, in turn, has impacts on weather patterns such as the Monsoon rains over Southeast Asia.

Highlighted are the years in which wet season rainfall was affected by El Niños, according to the 3-month mean of the Oceanic Niño Index (ONI) published by NOAA.

El Niño is a periodic natural phenomenon, which has been continuously observed over the past 120 years. But here, climate change enters the equation for the second time.

Scientists warn that global warming could exacerbate El Niño to make the events positively devastating. A study published in Nature Geoscience in 2019 assessed the last 400 years of El Niño on the basis of coral reef growth. Its results show that in recent decades, the events have grown both more frequent and more severe.

Climate change is thought to be a major contributing factor.

The effects of anthropogenic climate change on the Mekong basin are undeniable. But humans also have more direct impacts on the delta, which further aggravate floods droughts.

First and foremost, hydropower projects have been increasingly damming up the Mekong and its tributaries.

The first dams were built in the 1960s, and for decades both the number of dams and the amount of river water they held back remained limited. But in the early 2000s, the number of dams and their capacity skyrocketed. In 2005, there were 16 dams on the Mekong and its tributaries. Today, there are nearly 100. Another 30 are currently under construction.

Overall, hydropower stations in the Mekong basin have the potential to generate 13,000 MW of electricity—more than enough to power the whole of New York City. According to a 2018 study, the percentage of river water stored for hydropower will rise tenfold from 2% in 2008 to almost 20% in 2025.

2019 also saw the opening of Xayaburi in Laos, the first of eleven dams built directly on the Mekong mainstream. Its construction originally began in 2012 but was fraught with complaints from environmentalists and citizens’ groups.

Many local residents believe that the drought suffered in downstream countries was a direct consequence of the newly opened dam. Even though a panel of experts invited to observe the dam’s functioning by its operator concluded in February 2020 that it was not a factor contributing to the drought, a Thai activist initiative submitted evidence to the contrary the very same week.

A second dam in the series, Don Sahong, began operating in Laos in January 2020, just upstream of the border to Cambodia.

The Mekong River Commission (MRC), an intergovernmental body created to “jointly manage the shared water resources and the sustainable development of the Mekong River”, attempts to mediate water use conflicts. But it still appears that dam operators optimize their water usage for power generation, with little regard for downstream effects.

The predominance of hydropower projects is also a result of Chinese influence over Southeast Asia. Chinese companies and government initiatives invest heavily in infrastructure projects in countries like Laos and Cambodia. Local politicians welcome funding with open arms, seeing it as a safeguard for both their citizens’ prosperity and their own political future.

Another factor that further exacerbates the adverse effects of climate change in Southeast Asia is land use.

In recent years, natural vegetation has been removed from vast swaths of land, and agriculture has been intensified. The spread of urban centers like Phnom Penh and Ho Chi Minh City has swallowed up huge tracts of land. Cumulatively, the modified land surface contributes to hydrological imbalances.

Temperatures increase as sunlight is absorbed by urban areas and open fields rather than reflected by natural vegetation. Evapotranspiration increases and ever-larger quantities of water are needed for irrigation.

The droughts that have haunted the Mekong delta ever more frequently in recent decades can be traced back to all these developments: rising temperatures, changing land management, the construction of hydropower dams, and the El Niño events aggravated by climate change on a global scale.

Rising Seas and Sinking Lands

While the floodplains of the delta are left parched by late, short floods, there is more trouble on the horizon: The delta as a whole is sinking, with the sea encroaching inland. For this phenomenon, too, there is a complex web of reasons.

Sea levels are rising globally.

Higher temperatures are melting glaciers worldwide, including the vast ice sheets of Antarctica and Greenland. In August 2019, images of meltwater torrents in Greenland went around the globe, with scientists calculating that ice was being lost at a record rate of 12.5 billion tons a single day. On February 7, 2020, temperatures of 18.3 °C were measured in Antarctica—the highest values ever recorded.

Another factor contributing to sea-level rise is the thermal expansion of ocean water. The higher the water temperature, the larger the volume that water molecules take up. Currently, the warming of ocean water mostly affects the upper water layers.

Data from the US National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) shows that over the past 100 years, average surface temperatures of oceans around the world have risen by 0.13 °C per decade. And the future is looking grim. Studies modelling scenarios of ocean warming, published in reports by the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change (IPCC), show that ocean temperatures could increase by another 1 – 4 °C by 2100.

How high precisely the sea levels are going to rise as a result of these developments is not yet clear. So far, measurements based on satellite data and gauges from across the world, indicate that the average sea level has increased by 7–8 inches since 1900. The scale of future increases depends, ultimately, on the success of measures taken to combat global warming. Currently, scientists are expecting global sea levels to rise by up to 8 feet by 2100.

Oceanographers and climatologists at NOAA have developed six scenarios for future Global Mean Sea Levels (GMSL). These scenarios are based on the projected greenhouse gas emissions, depending on how humans decide to handle climate change. Going a step further, the scientists assigned likelihoods to each of the scenarios.

In the most likely scenario, they calculated, global average sea-level rise by the end of this century will tally in at 3.3 feet.

This spells doom for coastal populations around the world, but especially for deltas, where the land is only a few feet above sea level. Here, minimal increases can have effects far inland.

The situation in the Mekong delta is particularly dire.

A 2019 study published in Nature Communications found that previous research calculating the negative impact of rising sea levels on the delta have underestimated it. Based on calculations using a refined elevation model, the scientists discovered that the average elevation of the Mekong delta is only 2.6 feet above sea level.

A sea level rise of 3.3 feet until 2100, as projected by NOAA, would flood the Vietnamese part of the delta entirely and displace over 18 million people.

In addition to these global developments, local factors are also influencing how coastal regions will be affected by rising sea levels. In some areas, tectonic movements are actually raising land faster than sea levels rise. This is the case in southeast Alaska, where the local sea levels are falling.

In other regions, such as the Mekong delta, the reverse is true.

While the sea is rising, the land is also sinking due to a process called subsidence. In this process, a landscape loses elevation either because sediments are being compacted, or because subterranean voids collapse. These voids can either exist naturally, such as cave systems in limestone, or result from human activities like oil, sand, or groundwater extraction.

In the Mekong delta, some land subsidence is natural, caused by tectonics and the settling of sediments deposited by the river since the last Ice Age. The majority, however, can be traced back to human activities.

The expanding infrastructure of the urban centers in the region is heavy, literally putting pressure on the delta and accelerating compaction. At the same time, the groundwater bodies in the Vietnamese Mekong delta are among the most heavily exploited in the world.

After Vietnam’s transition to a market economy in 1986, economic growth increased the need for water. Groundwater is used for domestic, agricultural and industrial purposes.

In 2017, a study using a 3D hydro-geological model found that over the past 25 years, the land has sunk by an average of 7 inches. Currently, around 660 million gallons of groundwater are being extracted from the Vietnamese Mekong delta every single day.

Subsidence due to groundwater extraction is extremely dangerous because it continues even after the end of the practice. A 2020 study found that even when stopping all groundwater extraction as quickly as possible, and implementing mitigation measures, the land would lose at least another 6 inches of elevation until 2100.

Far from being reduced, groundwater extraction increases by 4% every year. If unchecked, the subsidence by the end of the century could tally in at over three feet.

Again, rising sea levels and land subsidence are not the only elements in the equation. They are tightly interlinked with other aspects of global warming and power generation.

Higher temperatures and more frequent droughts have increased the demand for irrigation, in turn revving up the groundwater extraction rate.

Dams not only hold water back in upstream reservoirs, but also trap sediment. This sediment would usually be deposited on the floodplains, somewhat counteracting subsidence.

Economic interests are also eating away at the delta. According to recent research published in Nature, sand is being extracted at record rates from the delta. Enormous amounts are used to produce concrete for infrastructure development.

All this leaves the Mekong delta set to disappear beneath the waves.

Already, effects are felt today: Storm floods are sweeping across the delta ever more frequently, and much farther inland than before. The coastline, renowned for its beauty and a popular tourist destination, is slowly eroding away. Salty seawater encroaches into the river system, tilting the balance in ecosystems, and threatening agriculture and freshwater fisheries.

A UN report released in February 2020 outlines the threats of the compound effects of droughts and saltwater intrusion in the Vietnamese Mekong Delta. It also warns of the destructive societal impacts, ranging from children being pulled out of school, to a sharp rise in poverty rates. In a worst-case scenario, estimates in February said, saltwater would intrude up to 44 miles inland.

But by mid-March, the situation had deteriorated even further, and saltwater intrusion reached 68s miles inland—19 miles further than the previous maximum. As a result, almost 40,000 hectares of rice paddies were destroyed. When the crisis peaked in early April, over 95,000 households were affected, experiencing shortages of drinking water or even a total lack thereof.

Faced with such current reminders of the fragility of the situation, the future gives cause for worry.

What Will the Future Hold?

The degree to which the present crisis in the Mekong delta will morph into a future catastrophe is not yet certain. Many of the projections on which future scenarios are based are still wide open to human influence, on a local, regional, and global level.

Locally, many communes in the delta are arming against droughts and salinity intrusion through infrastructure developments. They are constructing sluice gates to restrict the inflow of salty water during the dry season, and extending water distribution systems. Farmers are increasingly also switching their crops to drought- and salt-resistant varieties.

On a regional and national level, measures could be taken to tackle the problems at their sources. Reducing the rates of groundwater extractions to restrict land subsidence, developing information campaigns, emergency plans, and regulations to coordinate irrigation and reduce saltwater intrusions are all steps that have been suggested. The adverse effects of the upstream dams might be mitigated through diplomacy.

Unfortunately, economic interests still largely outweigh the political will for such measures.

Ultimately, the future of the delta also hinges on the willingness of the international community to commit to combating global warming by reducing emissions. Even if all possible measures were taken in the Mekong delta itself, sea-level rise could still result in the delta’s disappearance, if not limited by international action.

Some consequences have already become irreversible, such as a certain amount of land subsidence, or a globally increased frequency of El Niño events.

But right now, there is still a chance to create a sustainable future for the Mekong delta and its inhabitants. The question is whether the delta’s inhabitants, its political leaders, and the global community as a whole are willing and able to take the steps needed to grasp this chance.